Roots (1736–1816)

The United Methodist Church shares a common history and heritage

with other Methodist and Wesleyan bodies. The lives and ministries of

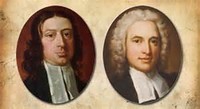

John Wesley (1703–1791) and of his brother, Charles (1707–1788),

mark the origin of their common roots. Both John and Charles were

Church of England missionaries to the colony of Georgia,

arriving in March 1736.

It was their only occasion to visit America.

Their mission was far from an unqualified success,

and both returned to England disillusioned and discouraged,

Charles in December 1736, and John in February 1738.

Both of the Wesley brothers had transforming religious experiences in May 1738. John’s heart “was strangely warmed”

at a prayer meeting on Aldersgate Street in London. In the years following, the Wesleys succeeded in leading a lively renewal movement in the Church of England. As the Methodist movement grew, it became apparent that their ministry would spread to the American colonies as some Methodists made the exhausting and hazardous Atlantic voyage to the New World.

Organized Methodism in America began as a lay movement. Among its earliest leaders were Robert Strawbridge, an immigrant farmer who organized work about 1760 in Maryland and Virginia, Philip Embury and his cousin, Barbara Heck, who began work in New York in 1766, and Captain Thomas Webb, whose labors were instrumental in Methodist beginnings in Philadelphia in 1767. African Americans participated actively in these groundbreaking and formational initiatives though much of that contribution was acknowledged without much biographical detail.

To strengthen the Methodist work in the colonies, John Wesley sent two of his lay preachers, Richard Boardman and Joseph Pilmore, to America in 1769. Two years later Richard Wright and Francis Asbury were also dispatched by Wesley to undergird the growing American Methodist societies. Francis Asbury became the most important figure in early American Methodism. His energetic devotion to the principles of Wesleyan theology, ministry, and organization shaped Methodism in America in a way unmatched by any other individual. In addition to the preachers sent by Wesley, some Methodists in the colonies also answered the call to become lay preachers in the movement.

The first conference of Methodist preachers in the colonies was held in Philadelphia in 1773. The ten who attended took several important actions. They pledged allegiance to Wesley’s leadership and agreed that they would not administer the sacraments because they were laypersons. Their people were to receive the sacraments of baptism and the Lord’s Supper at the local Anglican parish church. They emphasized strong discipline among the societies and preachers. A system of regular conferences of the preachers was inaugurated similar to those Wesley had instituted in England to conduct the business of the Methodist movement.

The American Revolution had a profound impact on Methodism. John Wesley’s Toryism and his writings against the revolutionary cause did not enhance the image of Methodism among many who supported independence. Furthermore,

a number of Methodist preachers refused to bear arms to aid the patriots.

When independence from England had been won, Wesley recognized that changes were necessary in American Methodism. He sent Thomas Coke to America to superintend the work with Asbury. Coke brought with him a prayer book titled The Sunday Service of the Methodists in North America, prepared by Wesley and incorporating his revision of the Church of England’s Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion. Two other preachers, Richard Whatcoat and Thomas Vasey, whom Wesley had ordained, accompanied Coke. Wesley’s ordinations set a precedent that ultimately permitted Methodists in America to become an independent church.

In December 1784, the famous Christmas Conference of preachers was held in Baltimore at Lovely Lane Chapel to chart the future course of the movement in America. Most of the American preachers attended, probably including two African Americans, Harry Hosier and Richard Allen. It was at this gathering that the movement became organized as The Methodist Episcopal Church in America.

In the years following the Christmas Conference, The Methodist Episcopal Church published its first Discipline (1785), adopted a quadrennial General Conference, the first of which was held in 1792, drafted a Constitution in 1808, refined its structure, established a publishing house, and became an ardent proponent of revivalism and the camp meeting.

As The Methodist Episcopal Church was in its infancy, two other churches were being formed. In their earliest years they were composed almost entirely of German-speaking people. The first was founded by Philip William Otterbein (1726–1813) and Martin Boehm (1725–1812). Otterbein, a German Reformed pastor, and Boehm, a Mennonite, preached an evangelical message and experience similar to the Methodists. In 1800 their followers formally organized the Church of the United Brethren in Christ. A second church, The Evangelical Association, was begun by Jacob Albright (1759–1808),

a Lutheran farmer and tilemaker in eastern Pennsylvania who had been converted and nurtured under Methodist teaching. The Evangelical Association was officially organized in 1803. These two churches were to unite with each other in 1946 and with The Methodist Church in 1968 to form The United Methodist Church.

By the time of Asbury’s death in March 1816, Otterbein, Boehm, and Albright had also died. The churches they nurtured had survived the difficulties of early life and were beginning to expand numerically and geographically.

From The Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church - 2012. Copyright 2012 by The United Methodist Publishing House. Used by permission.

Info from; www.UMC.org